European Union Critical Infrastructure (#CI) law for Dummies - an easy to understand guide on key EU Directives.

Context:

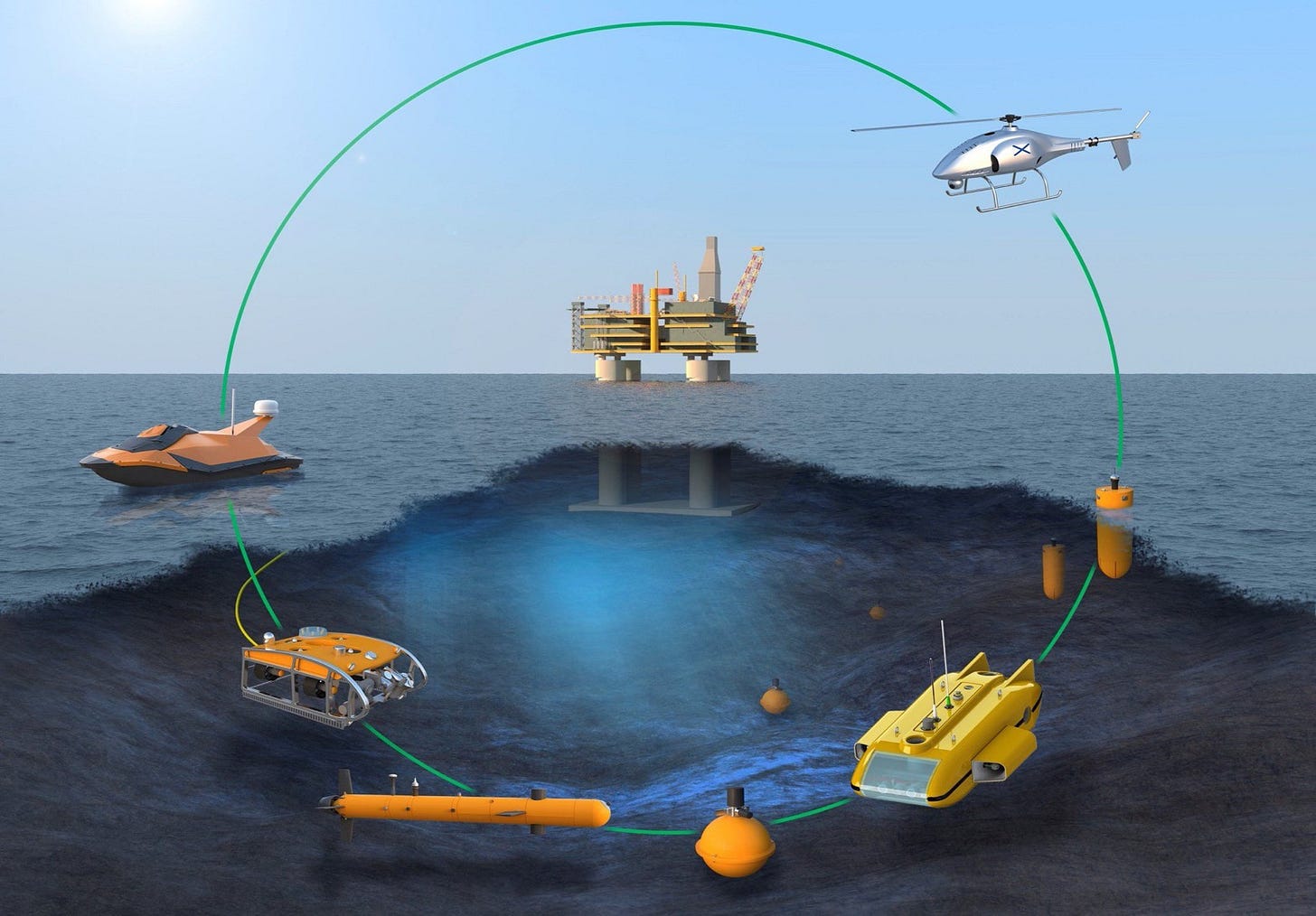

The West’s Undersea #Critical #Infrastructures (CI’s) s are a new frontier of warfare.

Critical infrastructure is an attractive target both for Ukraine in its fight against an invading aggressor, and by Russia who tries by all unorthodox means to disrupt energy and communication infrastructure across the globe.

Given the difficulty of attributing such attacks and the lack of immediate fatalities, which reduces the likelihood of escalation or retaliation. It includes energy assets, onshore and offshore, plus transport and data systems.

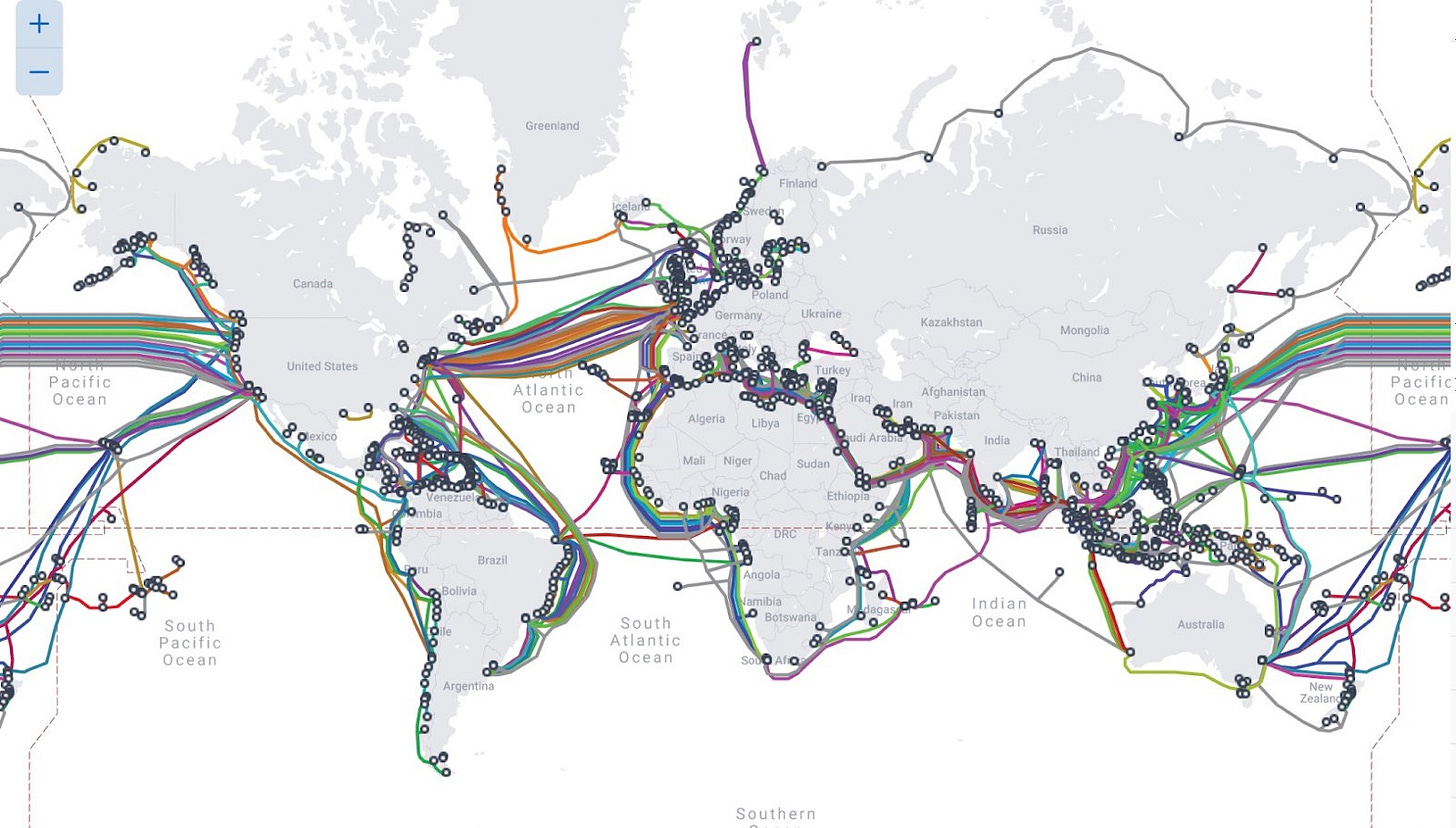

Europe’s and the world’s dependence on a limited number of fibre-optic cables that form the global internet network and links the continents worldwide and islands, has become a rising security concern in the light of new geopolitical conflicts.

At present, 95 percent of international internet traffic is transmitted by around 200 major #undersea #cables – each cable capable of data transfer at about 200 terabyte per second – supplemented by another 340. These cables carry an estimated US$10tn worth of financial transactions every day. They are interconnected at just 10 international, but vulnerable chokepoints. Following the sabotage of the Nord Stream Pipeline around September 26, 2022 - the EU responded to the event as a wake-up call.

The EU quickly recognised it is facing increased threats towards its CIs amid the war in Ukraine and has heightened attention to new hybrid security risks as well as infrastructural resilience in particular.

Both the European Parliament and the European Council had already agreed prior to the pipeline assault to deepen the legislative framework to strengthen the resilience of entities operating CIs.

97% of global communications and $10 trillion in daily financial transactions are transmitted not by satellites in the skies, but by cables lying deep beneath the ocean. Undersea cables are the indispensable infrastructure of our time, essential to our modern life and digital economy, yet they are inadequately protected and highly vulnerable to attack at sea and on land, from both hostile states and terrorists.

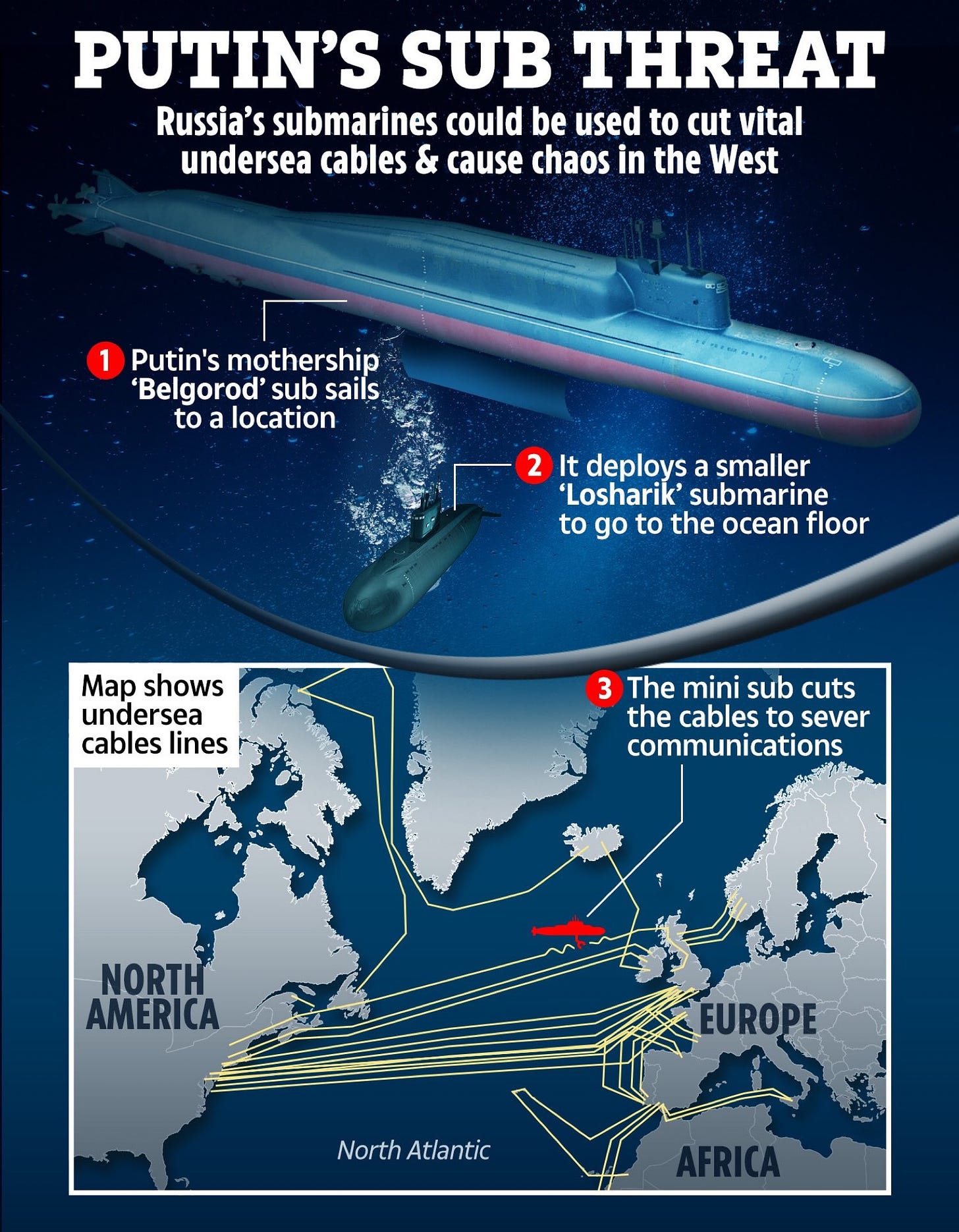

US intelligence officials have spoken of Russian submarines “aggressively operating” near Atlantic cables as part of its broader interest in unconventional methods of #warfare. When Russia annexed Crimea, one of its first moves was to sever the main cable connection to the outside world.

Undersea cables come ashore in just a few remote, coastal locations. These landing sites are critical national infrastructure but often have minimal protection, making them vulnerable to terrorism. A foiled Al-Qaeda plot to destroy a key London internet exchange in 2007 illustrates the credibility of the threat.

Since the first trans-Atlantic cable laid in 1858, cables have mainly been installed and owned by private companies. Although positive for taxpayers, this has meant undersea cables do not get the attention from governments they deserve.

Next 👉

🛟

In 2008 the EU described the directive’s intention as follows:

“The quality of life of EU citizens and their security, as well as the correct and efficient functioning of the internal market, depend on the provision of essential services through different critical infrastructures in a wide range of sectors.

It is therefore imperative that critical infrastructures are adequately protected against a wide spectrum of threats, both natural and man-made, unintentional and with malicious intent.

Where this fails and disruptions nevertheless follow, critical infrastructures must be resilient, i.e. able to recover quickly within an acceptable amount of time. As a reflection of the importance of this issue, the Commission adopted in 2006 the European Programme for Critical Infrastructure Protection (#EPCIP), which sets out a European-level all-hazards framework for critical infrastructure protection (#CIP).”

Council #Directive 2008/114/EC provides for a procedure for designating European critical infrastructure in the energy and transport sectors the disruption or destruction of which would have a significant cross-border impact on at least two Member States. That Directive focuses exclusively on the protection of such infrastructure.

However, the evaluation of Directive 2008/114/EC conducted in 2019 found that, due to the increasingly interconnected and cross-border nature of operations using critical infrastructure, protective measures relating to individual assets alone are insufficient to prevent all disruptions from taking place.

Therefore, it is necessary to shift the approach towards ensuring that risks are better accounted for, that the role and duties of critical entities as providers of services essential to the functioning of the internal market are better defined and coherent, and that Union rules are adopted to enhance the resilience of critical entities.

Critical entities should be in a position to reinforce their ability to prevent, protect against, respond to, resist, mitigate, absorb, accommodate and recover from incidents that have the potential to disrupt the provision of essential services.

While a number of measures at Union level, such as the European Programme for Critical Infrastructure Protection, and at national level aim to support the protection of critical infrastructure in the Union, more should be done to better equip the entities operating such infrastructure to address the risks to their operations that could result in the disruption of the provision of essential services.

More should also be done to better equip such entities because there is a dynamic threat landscape, which includes evolving hybrid and terrorist threats, and growing interdependencies between infrastructure and sectors.

Next 👉

🛟 The other piece of EU legislation around critical infrastructure is through the Critical Entities Resilience Directive (#CER) of 2022:

The Critical Entities Resilience Directive lays down obligations on #EU Member States to take specific measures, to ensure that essential services for the maintenance of vital societal functions or economic activities are provided in a. unobstructed manner in the internal market.

While certain sectors of the economy, such as the energy and transport sectors, were already regulated by sector-specific Union legal acts, those legal acts contained provisions which related only to certain aspects of resilience of entities operating in those sectors.

In order to address in a comprehensive manner the resilience of those entities that are critical for the proper functioning of the internal market, the Critical Entities Resilience Directive creates an overarching framework that addresses the resilience of critical entities in respect of all hazards, whether natural or man-made, accidental or intentional.

Critical entities must have a comprehensive understanding of the relevant risks to which they are exposed, and a duty to analyse those risks.

To that end, they must carry out risk assessments in view of their particular circumstances and the evolution of those risks and, in any event, every four years, in order to assess all relevant risks that could disrupt the provision of their essential services (‘critical entity risk assessment’).

On July 25, 2023 - the EU Commission delagated regulation supplementing Directive (EU) 2022/2557 by establishing a list of Non-exhaustive list of essential services, including the likes of the

👉 energy sector: sub-sectors of Electricity, Gas and Oil infrastructure - along with many others in the list

👉 transportation sector: sub sector of digital (coms) sector.

Next 👉

Understanding the Critical Entities Resilience Directive (CER), from the proposal of 16.12.2020

Key Articles:

Article 1 sets out the subject matter and scope of the directive, which lays down obligations for Member States to take certain measures aimed at ensuring the provision in the internal market of services essential for the maintenance of vital societal functions or economic activities, in particular to identify critical entities and to enable them to meet specific obligations aimed at enhancing their resilience and improving their ability to provide those services in the internal market.

The directive also establishes rules on supervision and enforcement of critical entities and the specific oversight of critical entities considered to be of particular European significance.

Article 3 states that Member States shall adopt a strategy for reinforcing the resilience of critical entities, describes the elements that it should contain, explains that it should be updated regularly and where necessary, and stipulates that Member States shall communicate their strategies and any updates of their strategies to the Commission.

Article 4 states that competent authorities shall establish a list of essential services and carry out regularly an assessment of all relevant risks that may affect the provision of those essential services with a view to identifying critical entities. This assessment shall account for the risk assessments carried out in accordance with other relevant acts of Union law, the risks arising from the dependencies between specific sectors, and available information on incidents.

Member States shall ensure that relevant elements of the risk assessment are made available to critical entities, and that data on the types of risks identified and the outcomes of their risk assessments is made regularly available to the Commission.

Article 5 states that Member States shall identify critical entities in specific sectors and sub-sectors. The identification process should account for the outcomes of the risk assessment and apply specific criteria. Member States shall establish a list of critical entities, which shall be updated where necessary and regularly. Critical entities shall be duly notified of their identification and the obligations that this entails.

Competent authorities responsible for the implementation of the directive shall notify the competent authorities responsible for the implementation of the NIS 2 Directive of the identification of critical entities.

Where an entity has been identified as critical by two or more Member States, the Member States shall engage in consultation with each other with a view to reduce the burden on the critical entity. Where critical entities provide services to or in more than one third of Member States, the Member State concerned shall notify to the Commission the identities of those critical entities.

Next 👉

How does NATO fit into the framework of Critical Infrastructure protection, bleeding into EU member states?

NATO is not ready to mitigate increasingly prevalent Russian aggression against European critical undersea infrastructure (CUI). Despite its depleted ground forces and strained military industrial base, Russian hybrid tactics remains the most pressing threat to CUI in northern Europe.

Despite its current limitations, NATO is the primary actor capable of deterring and preventing hybrid attacks on its allies and has expedited its approach to CUI protection by establishing new organizations to that aim.

At the 2023 NATO Vilnius summit, allies agreed to establish the Maritime Centre for the Security of Critical Underwater Infrastructure within NATO’s Allied Maritime Command (MARCOM), which focuses on preparing for, deterring, and defending against the coercive use of energy and other hybrid tactics.

The war in Ukraine has radically altered the threat landscape across Europe, particularly in the north. As the alliance remains focused on supporting Ukraine and shoring up its eastern flank, Sweden’s and Finland’s membership bids will provide new opportunities to deter Russian aggression in the Baltic and Arctic regions.

But recent examples of CUI interference highlight vulnerabilities that will not be easily remedied. The sabotage of two Nord Stream pipelines off the Danish island of Bornholm in September 2022 forced European governments to grapple with their limited ability to deter and defend against hybrid tactics in the undersea domain.

Recent damage to the Balticconnector gas pipeline and a data cable between Finland and Estonia in October 2023 from a ship’s anchor is suspected as being deliberate, although attribution has not yet been declared.

Russian hybrid tactics represent the most pressing threat to CUI in northern Europe. Russia’s war against Ukraine has debilitated its ground forces and strained its military industrial base.

Experts estimate it will take the Kremlin five to ten years to reconstitute its military. Meanwhile, however, Russia’s power projection capabilities in northern Europe—through naval, air, and missile bases in Kaliningrad and its Northern Fleet of submarines on the Kola Peninsula—have scarcely been depleted.

In fact, while the Russian navy is underfunded and a large part of its fleet comprises Soviet legacy platforms, its underwater capacity continues to grow. In particular, Russia’s submarine program remains a priority amid other military budget cuts, exemplified by the Kremlin’s authorization of 13 new nuclear and conventional submarines since 2014.

In broader terms, Russia’s ability to target critical infrastructure short of war and impose economic costs to deter external intervention in regional conflicts is an important component to Moscow’s doctrine and thinking on escalation management.

However, even in the absence of a broader Russia-NATO conflict, hybrid tactics have been a staple in the Kremlin’s toolbox in Europe for years. As the Kremlin views itself in perpetual conflict with the West, hybrid tactics are instrumental to challenging #NATO without resorting to conventional military means.

Russia has likely targeted critical infrastructure throughout Europe at an increased frequency since its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In the undersea domain, Russia appears committed to mapping and threatening European energy and communications infrastructure, particularly strategically important Norwegian gas pipelines and fiber-optic cables.

Next 👉

Protecting Critical Undersea Infrastructure: A New Focus For NATO

While many stakeholders have increased their efforts to protect CUI, NATO remains the lead actor when it comes to deterring and preventing conventional and hybrid attacks on allies.

NATO’s role in protecting CUI is grounded in its founding principles, such as Articles 2 and 3 of the North Atlantic Treaty, which call for the strengthening of free institutions, economic collaboration, and growing resilience to attack. At the 2023 Vilnius summit, allies reiterated that hybrid operations against the alliance could meet the threshold of armed attack and trigger Article 5, NATO’s collective defense guarantee.

NATO’s New Centers

In response to recent incidents in the Baltic Sea, NATO has expedited its approach to CUI protection by establishing two new organizations. In February 2023 the Critical Undersea Infrastructure Coordination Cell was created at NATO headquarters.

The rationale was to coordinate allied activity; bring military and civilian stakeholders together by facilitating engagement with private industry, which owns much of the infrastructure; and better protect CUI through jointly detecting and responding to threats. This new cell will be instrumental in building coordination across all the organizations, policies, and capabilities identified in Table 1 both within and external to NATO.

Then, at the July 2023 Vilnius summit, allies agreed to establish the Maritime Centre for the Security of Critical Underwater Infrastructure within NATO’s Allied Maritime Command (MARCOM).

This new center focuses on "identifying and mitigating strategic vulnerabilities and dependencies . . . to prepare for, deter and defend against the coercive use of energy and other hybrid tactics by state and non-state actors. . . . NATO stands ready to support Allies if and when requested."

The center arrives at a crucial time for NATO as both new threats to CUI and new initiatives to deal with them proliferate across the alliance and beyond. To help NATO planners and staff at the new center conceptualize and prioritize their efforts, the next section considers in more detail the problem of protecting #CUI.

This post does not cover all of the salient issues and legislation - I hope it provides an insight into some of the significant issues and provisions, and gives you a starters knowledge on the relevant legislation. This is twatter, and this level of detail is rarely offered, or indeed read on social media. I expect the majority of readers to skim read or pass on by, which is understandable for the medium. If you got this far, my hat is of to you!

6/6

For my visually impaired followers - use the response link to this tweet for an audio narration: https://t.co/QERPwdPa16

Please retweet if you enjoyed this - it helps with visibility ! Buy me a Coffee if you can, to help keep my work going!

👇 👇 👇 👇 👇 👇 👇 👇 👇 👇 👇 👇 👇 👇

https://buymeacoffee.com/beefeaterfella

🫶 Every single Coffee helps, sharing is important too! 🫶

References and sources:

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2008:345:0075:0082:en:PDF

https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/whats-new/european-critical-infrastructure_en

https://energypost.eu/russia-ukraine-critical-infrastructure-protection-from-sabotage-is-an-unprecedented-challenge-the-eu-must-face-now/

https://s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/files.cnas.org/documents/CNAS-Report-Russian-Vulnerabilities-Dec23_Final-1.pdf#page=28

https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/OXAN-DB278095/full/html

https://www.csis.org/analysis/natos-role-protecting-critical-undersea-infrastructure

https://policyexchange.org.uk/publication/undersea-cables-indispensable-insecure/

https://www.critical-entities-resilience-directive.com/

This is a subject area that is of not just national but global importance and it rarely receives attention from the MSM. The integrity of these systems is essential. Increasingly, russia is resorting to hybrid warfare in an attempt to disrupt and destabilise the Western alliance