Dummies guide to the rise and fall of the Ruble exchange rate

The winners and the losers in Russia - and the Ruble’s link to global energy prices.

Dummies guide to the implications of a falling and rising Ruble/$USD and the Ruble link to global energy prices. This thread explains the effect of a rising Ruble and a falling global oil price. The thread does not cover the Kremlin’s market manipulation of the value of the Ruble, it often intervenes in the market when the Ruble value is falling for a number of reasons, including to protect themselves from negative sentiment by Russians.

The thread sets out the winners and losers inside Russia with the rise and fall of the Ruble, it’s implications on the financing of the illegal war in Ukraine - and the movement of the Ruble being linked to global oil energy prices.

Weakening Ruble (more Ruble per USD) - the winners and the losers.

Who wins and — especially — who loses inside Russia from a weaker ruble, and how this connects to the effect of rising OPEC supply and falling oil prices on Russia’s export receipts and the Kremlin’s ability to finance the war in Ukraine.

A weaker ruble has complicated and often contradictory effects across Russia’s wartime economy. At a glance, depreciation can help some export-oriented firms and the state’s budget (when export receipts are paid in dollars) but it also amplifies inflation, raises the domestic cost of imports and foreign-currency liabilities, and erodes living standards — placing outsized pain on ordinary households, import-dependent firms and sectors that rely on foreign technology and finance.

Winners:

The immediate beneficiaries of a weaker ruble are firms that earn hard currency and pay most of their costs in rubles: commodity exporters (where global prices remain favourable), parts of heavy industry that sell abroad, and some exporters of manufactured goods able to price competitively in foreign markets.

A depreciation can mechanically raise local-currency revenue from the same dollar receipts, improving nominal profits and cash flows for such firms and easing the government’s need for ruble financing if it receives oil and gas proceeds in dollars and converts them locally. Empirical work and past Russian episodes show exporters’ competitiveness improves when the ruble weakens.

Losers:

The losers from a sustained, material depreciation of the ruble fall into clear groups:

Households and consumers.

A weaker ruble raises the prices of imported goods and services (everything from consumer electronics and cars to medicines and some food items), squeezing real wages and pushing up headline inflation. For lower-income households — who spend a large share of income on staples and cannot easily substitute domestic for imported goods — this is particularly painful. Real purchasing power falls and poverty risks rise in the absence of offsetting social transfers. Central bank summaries and inflation data for 2024–25 show that exchange-rate pass-through remains a key channel driving prices in Russia.

Import-dependent firms and supply-chain nodes.

Retailers, carmakers, airlines, telecoms and manufacturers that use imported inputs see costs surge. For companies that cannot quickly re-source from domestic suppliers, margins compress; some must raise prices and lose market share. Firms holding inventory purchased in foreign currency suffer immediate balance-sheet hits; firms that import critical spare parts (e.g., for refineries, aircraft or precision machinery) face production disruptions and higher maintenance costs. Historical accounts of ruble crises demonstrate durable damage to sectors reliant on imported capital goods.

Borrowers with foreign-currency debt and financial counterparties.

Corporates and banks that carry USD- or euro-denominated liabilities see their ruble debt burden balloon after depreciation. Even if foreign funding is already restricted by sanctions, outstanding FX debt still exists for many firms (and for subsidiaries of foreign companies operating in Russia). A jump in ruble cost of servicing foreign debt raises default risk, forces fire sales and tightens credit conditions for investment and payroll. This amplifies stress across the private sector.

Savers and those with foreign-asset exposure.

Individuals and institutions holding savings denominated in foreign currency lose value in ruble terms; if capital controls are tightened, those losses are effectively irreversible. Pension funds and corporate treasuries with FX buffers may be forced to revalue or reallocate at an inopportune moment.

Import-competing consumer sectors and high-technology producers.

While a weaker ruble can help some domestic producers compete with imports, many sectors (notably high-tech, pharmaceuticals, precision engineering) depend on imported inputs, IP and software. These sectors lose twice: higher import costs and restricted access to critical foreign technology because of sanctions. That constrains long-term productivity and industrial modernisation.

Public-finance paradox and fiscal losers.

On paper, a weaker ruble can inflate the ruble value of oil and gas export receipts, which helps the budget in the near term. But that “benefit” is conditional: it only works if export volumes and USD prices are stable. When oil prices fall, the boost from currency conversion disappears — and can leave the state worse off. Recent public finance reporting indicates Russia has already cut 2025 energy revenue forecasts and raised its deficit outlook because oil prices are lower than assumed, forcing a revision of fiscal plans. That reduces the state’s fiscal headroom and may require cuts to non-priority spending or additional borrowing — outcomes that ultimately harm households and non-defence programs.

Strengthening Ruble (Less Rubles per USD) - the winners and losers:

A strengthening ruble — meaning fewer rubles are needed to buy one US dollar — has complex effects on Russia’s economy and war financing. While it can signal nominal stability and reduce inflationary pressure, it also erodes government revenues from exports priced in foreign currency. The balance of winners and losers thus cuts across social and institutional lines.

Winners:

Consumers and households

A stronger ruble lowers the domestic price of imported goods — from electronics and medicine to food and fuel — because fewer rubles are needed to pay for foreign products. Inflation moderates, purchasing power rises, and savings retain more real value. In an economy where consumer prices are highly sensitive to exchange-rate movements, an appreciating ruble temporarily improves living standards and eases social tensions.

Import-dependent firms

Companies relying on imported components, equipment, or foreign technology benefit directly. Their input costs fall, margins improve, and the pressure to “substitute imports” with lower-quality domestic alternatives weakens. Sectors such as aviation, machinery, IT, and pharmaceuticals particularly gain, as they remain reliant on Western spare parts and software despite sanctions and “parallel import” workarounds.

Borrowers with foreign-currency debt

A stronger ruble reduces the local-currency burden of repaying or servicing USD- or euro-denominated loans. Russian corporations and banks with residual external liabilities experience relief, freeing liquidity for operations and domestic investment.

Central Bank and inflation policy

The Bank of Russia benefits from reduced inflationary pressure and lower demand for emergency rate hikes. A stable or appreciating ruble supports confidence in the financial system and helps slow the outflow of capital into hard currencies.

Losers:

The Russian state and budget revenues

The government is the main loser when the ruble strengthens. Russia’s budget is denominated in rubles, but most state income — from oil, gas, and other commodity exports — is earned in dollars or euros. When those foreign revenues are converted into a stronger ruble, the domestic budget receives fewer rubles per dollar of export income.

This directly undermines the Ministry of Finance’s ability to meet rising fiscal needs — particularly military spending in Ukraine. For example, if oil prices remain flat while the ruble appreciates, total ruble-denominated oil-and-gas revenue falls, widening the deficit. Analysts at the Bank of Finland and Bloomberg Economics have repeatedly observed that each 10% ruble appreciation can cut ruble oil-and-gas revenues by 7–8%, depending on price levels.

Exporters (especially energy firms)

Exporters receive their revenues in foreign currencies but pay most expenses (wages, logistics, taxes) in rubles. A stronger ruble compresses their profit margins because their dollar receipts translate into fewer rubles. This effect is especially pronounced when global prices for oil, gas, and metals are stable or declining. For energy firms already selling oil at discounted prices due to sanctions and price caps, an appreciating ruble compounds the squeeze.

Regional and industrial subsidies

Lower export tax receipts mean less federal funding available for regional subsidies, pensions, and industrial support schemes. The Kremlin often prioritises defence spending, so social and civilian programmes absorb the fiscal strain first — hurting regional budgets and public investment.

Military financing and logistics

Russia’s ability to finance its “special military operation” depends heavily on export tax revenues. When the ruble strengthens and oil or gas prices decline, the ruble value of export earnings drops. This constrains the funds available for ammunition, procurement, and payments to soldiers and contractors. In recent months, the Russian Finance Ministry’s own reports (e.g. Reuters, April 2025) show that lower energy receipts and a stronger ruble have widened the fiscal deficit and forced higher domestic borrowing, increasing long-term costs.

The Strengthening Ruble & lower oil price Paradox: the positive implications for the war in Ukraine

A stronger ruble, combined with lower oil prices, reduces Russia’s budget inflows in ruble terms. Even if the Kremlin can still borrow domestically through “patriotic bonds” or the National Wealth Fund, those are finite buffers. As the ruble strengthens:

The government receives fewer rubles for each dollar of oil sold, shrinking fiscal space for weapons, logistics, and soldier pay.

Exporters’ tax contributions weaken, while social spending pressures persist.

The Ministry of Finance must issue more domestic debt or draw from reserves, increasing fiscal fragility.

In effect, an appreciating ruble makes war financing more difficult — not because it drains foreign exchange, but because it reduces the ruble value of the very foreign revenues used to fund war expenditures.

Summarising the rise and fall of the Ruble:

A stronger ruble stabilises consumer prices and comforts urban households, but it weakens the financial engine of the Russian state. Because Moscow’s war in Ukraine is heavily financed through energy exports, the ruble’s appreciation — especially when combined with lower oil prices due to OPEC’s increased output — undermines the government’s ability to sustain high levels of military spending.

What benefits the Russian consumer in the short term indirectly constrains the Kremlin’s long-term war budget.

The impact of energy prices on the Ruble:

How OPEC supply increases and falling oil prices change the picture. OPEC+ production decisions matter to Russia because oil and gas are the single largest external revenue source.

Across 2025 the alliance’s collective output targets have been raised (the group has increased output targets by millions of barrels per day this year), and forecasts of additional OPEC+ volume increases put downward pressure on Brent/Urals prices.

A larger global supply (or the prospect of a supply glut) depresses prices; lower oil prices reduce Russia’s dollar revenues even if the ruble depreciates. Several recent analyses and market reports show that revisions to OPEC+ output and an easing of voluntary cuts have been connected to lower prices and reduced Russian energy receipts.

Russia’s government finances are very sensitive to changes in global oil prices.

Last year, oil & gas earnings accounted for about 30 % of total federal revenues and 16 % of consolidated government revenues.

This year’s budget framework assumes that the average export price of Russian crude oil is $70 a barrel.

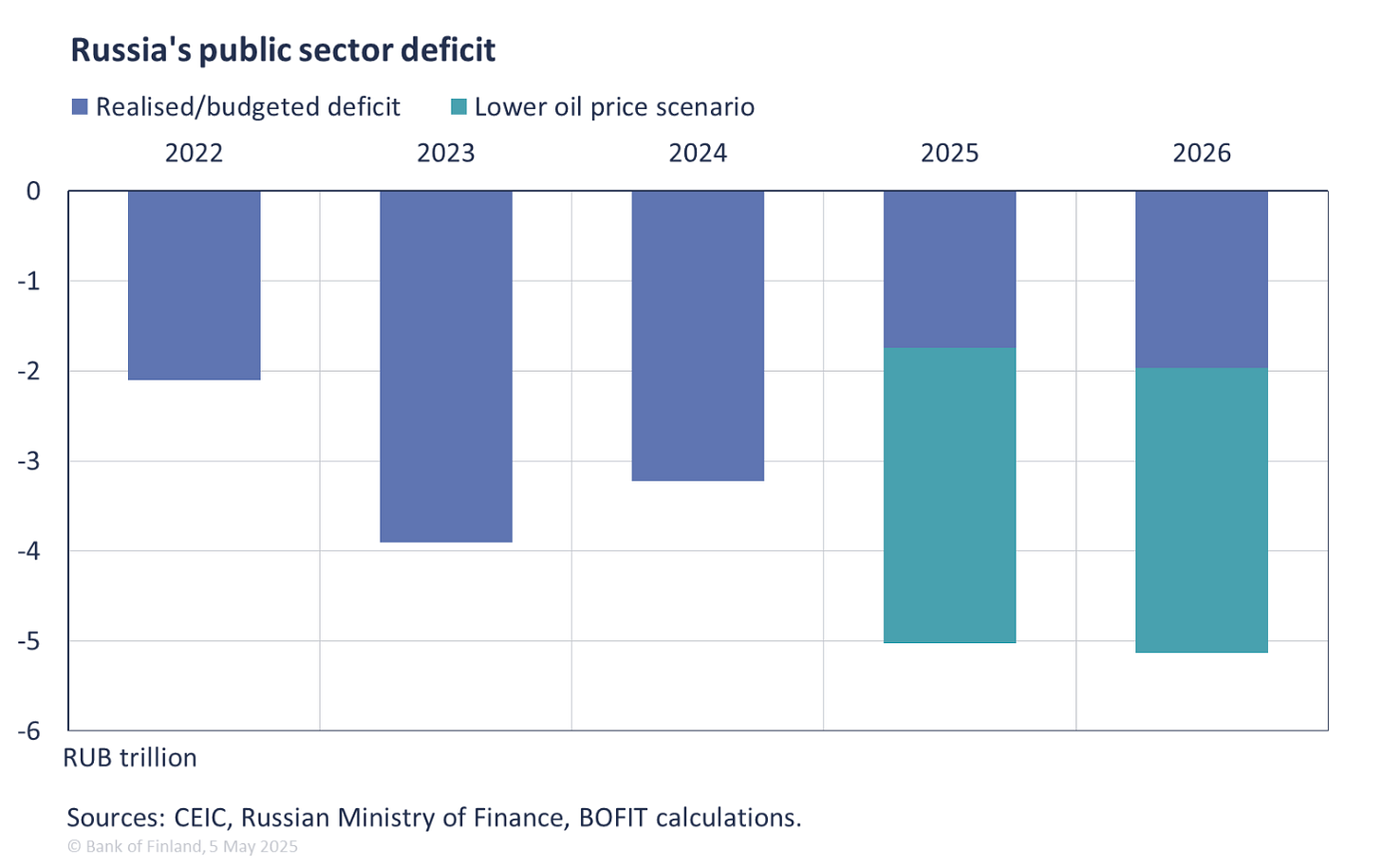

The 2026 budget assumes an average export price of $66 a barrel. The ruble’s average exchange rate this year is assumed to be 96.5 rubles to the US dollar and 100 rubles to the dollar next year. Under these assumptions, the budgeted deficit for the public sector would amount to 1.7 trillion rubles this year and 2 trillion rubles next year (a deficit of about 1 % of GDP each year).The International Energy Agency (IEA) reports that the export price of Russian oil averaged $63 a barrel during the first three months of this year.

Russian crude carried an average discount of $12 a barrel compared to the benchmark of North Sea Dated. If the discount on Russian oil remains the same, the average export price of Russian crude would be about $55 a barrel this year and $53 next year. For January-April, the average RUB-USD exchange rate has been 91 rubles per dollar, which is somewhat stronger than budget assumption. If the ruble’s average rate remains at its April level until the end of 2026, it would average 86 rubles to the dollar this year and 83 rubles next year.

Financing Russia’s illegal war in Ukraine:

Why that matters for Russia’s ability to finance the war. Russia’s fiscal space is heavily influenced by oil and gas receipts. Official and independent assessments in 2025 reported sizeable downgrades to projected energy revenues and a material widening of the projected budget deficit as oil price assumptions were revised downward.

Lower dollar receipts mean fewer foreign-currency inflows to be converted into rubles for budget spending; even a weaker ruble cannot fully offset a significant fall in dollar revenues if prices and/or volumes decline. That forces the Kremlin to choose between drawing down reserves, borrowing (domestic or external where possible), cutting spending, raising taxes, or reprioritising — and defence outlays have been treated as highly protected. The net effect: lower oil prices tighten the fiscal leash and reduce the margin for sustained, large-scale military spending over time.

In the current situation, a deficit totalling 10 trillion rubles could cause difficulties for Russia. Government finances have been running in deficit already three years. At the same time, government indebtedness has risen. Although Russia’s government debt is moderate (20 % of GDP) by international standards, debt-servicing costs have risen due to higher interest rates. Russia has also drained much of its savings from oil & gas earnings

Policy and tactical implications.

In the near term the Bank of Russia typically responds to steep depreciation by tightening monetary conditions (higher rates) to limit inflation, which imposes further pain on investment and the real economy. Structural responses (diversifying import channels, localising supply chains, targeted social support) blunt the worst social impacts but are slow and costly. International pressures — price caps, sanctions on shipping and finance — also interact with market dynamics to shape net revenue outcomes for Moscow.

Conclusion.

A weaker ruble helps some exporters and can temporarily inflate ruble receipts from unchanged dollar revenues. But the losers — households, import-dependent businesses, borrowers with FX liabilities, firms that need foreign technology, and longer-term growth prospects — are numerous and concentrated among ordinary consumers and small-to-medium enterprises. Crucially, when falling oil prices (driven by higher OPEC+ supply or weaker demand) cut dollar receipts, the superficial budgetary benefit of a weaker ruble vanishes: the Kremlin’s war-financing cushion is reduced, deficits widen and painful fiscal and monetary trade-offs intensify.

There is a positive correlation between oil price and ruble strength. When Brent (or global crude) prices rise, the ruble often appreciates (USD/RUB falls). Conversely, when oil prices drop, the ruble tends to depreciate (USD/RUB rises). Volatility amplifies co-movement.

Periods of sharp oil price drops (e.g. global shocks) coincide with abrupt ruble depreciation. The correlation is more evident in crisis periods when other factors (capital flight, risk premia, sanctions) intensify the linkage.

In times of major shocks (e.g. 2014–2015 oil collapse, sanctions episodes) the relationship can become more volatile. Interventions, capital controls or central bank actions may temporarily distort the co-movement. For example, in October 2014 Russia moved to a more floating exchange regime in response to pressure on the ruble.

Thus, the historical evidence supports the intuition: Russia’s currency is tightly linked to global energy markets, making it vulnerable to oil price swings. Thus, in recent years, the pattern arguably holds: falling oil prices tend to mean a weaker ruble (or higher USD/RUB), and that hurts Russia’s dollar income converted into rubles for budget purposes.

Sources References:

Reuters (2025, April 30) – Russia raises 2025 deficit forecast threefold due to low oil price risks

https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/russia-raises-2025-deficit-forecast-threefold-due-low-oil-price-risks-2025-04-30/

Bank of Finland Bulletin (2025, May 5) – Falling oil prices reduce Russia’s budget revenues

https://publications.bof.fi/handle/10024/53990

Brookings (2024) – With the ruble depreciation, “Made in Russia” could once more become a worldwide trademark

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/with-the-ruble-depreciation-made-in-russia-could-once-more-become-a-worldwide-trademark/

Reuters (2025, Oct 13) – Russian oil output continued to rise in September, OPEC data shows

https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/russian-oil-output-continued-rise-september-opec-data-shows-2025-10-13/

OilPrice.com (2025) – Russia’s Crude Oil Export Revenues Hit Two-Year Low as Prices Dip

https://oilprice.com/Latest-Energy-News/World-News/Russias-Crude-Oil-Export-Revenues-Hit-Two-Year-Low-as-Prices-Dip.html

Interfax (2025, August 14) – Export currency conversion rules for Russian exporters abolished

https://interfax.com/newsroom/top-stories/113273/

Russia raises 2025 deficit forecast threefold due to low oil price risks — Reuters, Apr 30, 2025.

https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/russia-raises-2025-deficit-forecast-threefold-due-low-oil-price-risks-2025-04-30/

OPEC+ opts for modest oil output hike as glut fears mount — Reuters, Oct 5, 2025.

https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/opec-poised-raise-oil-output-further-sources-say-2025-10-05/

Russian oil output continued to rise in September, OPEC data shows — Reuters, Oct 13, 2025.

https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/russian-oil-output-continued-rise-september-opec-data-shows-2025-10-13/

How to cut Russia’s oil revenue by $80 bln a year — Reuters Breakingviews, Oct 13, 2025.

https://www.reuters.com/commentary/breakingviews/how-cut-russias-oil-revenue-by-80-bln-year-2025-10-13/

Falling oil prices reduce Russia’s budget revenues — Bank of Finland Bulletin (May 5, 2025).

https://publications.bof.fi/handle/10024/53990

Summary of the Key Rate Discussion — Bank of Russia (May 21, 2025).

https://www.cbr.ru/eng/dkp/mp_dec/decision_key_rate/summary_key_rate_12052025/

With the ruble depreciation, “Made in Russia” could once more become a worldwide trademark — Brookings (analysis on ruble depreciation and sector effects).

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/with-the-ruble-depreciation-made-in-russia-could-once-more-become-a-worldwide-trademark/

Winners And Losers In Russia’s Currency Crisis — Worldcrunch (context and historical perspective).

https://worldcrunch.com/world-affairs/winners-and-losers-in-russia039s-currency-crisis/

Bank of Finland economic bulletin

https://www.bofbulletin.fi/en/blogs/2025/falling-oil-prices-reduce-russia-s-budget-revenues/

If you enjoy my threads, please consider supporting my work on Patreon or BuymeACoffee!

Thank You! to those who have supported me on Patreon or buymeacoffee, you are simply awesome.

buymeacoffee.com/beefeaterfella

patreon.com/Beefeater_Fella

beefeaterresearch.substack.com

Gosh Beefy, that's an awful lot to get my head around! All I can constructively add is that current food inflation stands at almost 9.5% thus proving your assertion that the russian consumer is certainly a loser! Meticulously researched as always